Global Future Cities podcast, Episode 2. Working with the SDGs in urban projects: delivery partner insights

The second episode of the Global Future Cities podcast dives into the programme from the perspective of its delivery partners. Monique Cranna, a Technical Director of Urban Planning at Zutari, speaks with Sertaç Erten, a Planning Services Lead at ARUP Turkey. Sertaç and Monique explain their relationship with the Global Future Cities Programme, walking listeners through the Çankaya Healthy Streets project in Ankara (Sertaç) and the Strategic Area Framework development for Johannesburg’s Soweto “Triangle” (Monique). Grounded in these specific projects, the conversation includes detailed accounts of roadblocks, solutions and lessons learned that have manifested in Çankaya and Soweto through the GFCP. Both practitioners comment on new strategies they implemented – with respect to public participation and stakeholder engagement, for example – that have been informed by their participation in the GFCP. The benefits of public procurement, widespread and diverse data collection, sustainability checklists and proactive local governance are also covered.

Further information and in-depth learnings from the Global Future Cities Programme’s experience are available in the two Programme's Narrative Reports “Partnering for Transformative SDG-Oriented Urban Development: Guidance for Multi-Partner Initiatives from the Global Future Cities Programme” and “Integrating the SDGs in Urban Project Design: Recommendations from the Global Future Cities Programme”.

Below is the transcript of the podcast. Please listen to the podcast here.

Hello and welcome to the Global Future Cities podcast brought to you by UN-Habitat for a better urban future. My name is Gregory Scruggs, and I will be your host for this three-part podcast that will take you inside the Global Future Cities Programme, a project of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme or UN-Habitat, and the United Kingdom's Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office or UK FCDO.

How can the Sustainable Development Goals change urban projects for the better? That's the subject of our conversations here on the Global Future Cities podcast.

Today, we are joined by two guests. Monique Cranna is the Technical Director for Urban Planning at Zutari and is based in Johannesburg, South Africa. Sertaç Erten is the Planning Services Lead at ARUP Turkey and is based in Istanbul. Monique, Sertaç, welcome to the Global Future Cities podcast.

Greg: Could you please introduce yourselves and tell us a little bit more about your relationship to the Global Future Cities Programme, such as what projects you were working on and the role of your particular firm in that project? Monique, perhaps you could start.

|

Monique: So, I'm an urban planner based in South Africa. I've had a little bit of experience all over the world in my years of experience, and I'm working for Zutari at the moment. We are one of the consortium members for the Future Cities South Africa program. More specifically, I'm the Project Leader for the Soweto Strategic Area Framework, which is looking to unlock economic development in Soweto in Johannesburg. |

|

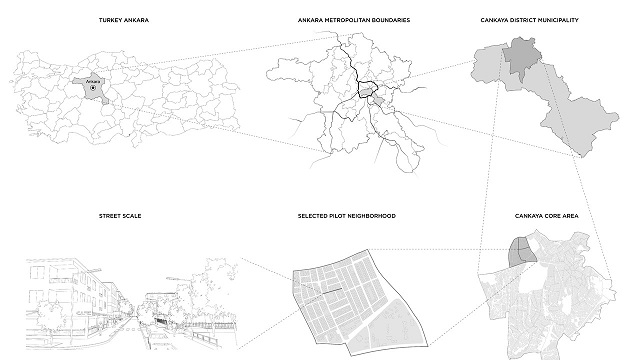

Sertaç: I am the Local Team Leader of Çankaya Healthy Streets Projects, which is one of the projects under the Global Future Cities Programme of UK FCDO and UN-Habitat. Çankaya is the Central District of Ankara, the capital of Turkey, and it is a very populated district. We as ARUP, as the delivery partner, have five projects conducted in Turkey, and among them, Çankaya healthy streets is the only urban design project with its neighbourhood scale and street scale solutions that are strongly linked to the SDGs. |

Greg: Wonderful. You both have long careers of experience in urban planning and design. How different from business as usual in the urban planning and design field is this practice through the Global Feature Cities Programme of incorporating SDG considerations into project planning and execution?

Sertaç: Well, first, let's define what is business as usual in urban planning and urban design. Urban design in countries like Turkey is seen and practiced as a bureaucratic activity of land management, mostly, and decision making in urban planning is mostly linked to issuing building permits, giving the construction rights, defining some land use zones for a growing settlement. And of course, this perspective limits the steps towards sustainable urbanisation. Because the focus is on a linear growing city and its allocation on urban land with urban services, and in the city model, there is generally a sectoral devolution of functions into housing, working, transportation, education, and like in compartments. Of course, this within this model, city model, urban design deals generally conventionally with spatial layout of the city three-dimensional organization of open public spaces, while, for instance, landscape design deals with trees planting, their maintenance, and planning department tries to produce blueprints of plants that will function for defining building permits and no building zones. So, this is for me business as usual. And first, this is a model which perceives the land and of course, the Earth as an unlimited source. And if cities become attraction points, then they will grow, they will have adequate capacity for motor vehicles, they will accommodate more people. And secondly, this perspective believes that everything is under control, and everything is external to this linear evolution of cities. It believes that to minimize all external risks like rainwater scarcity, earthquake drought, we should build the right engineering, right infrastructure, the right amount of allocation of land to solve the problems. And when there is a range of issues like emergencies, like sudden weather events as we are experiencing right now, or unexpected conditions like COVID 19 pandemic, then this linearity, this vision, this city model, is the business as usual, and it doesn't work at all. And we need more than this vision. We need focused strategic interventions carefully tailored to specific demands of cities right now. We should consider the most vulnerable groups who will be affected with these changes of cities, and within this perspective, incorporating SDG considerations into urban planning practices as well as urban design projects of municipalities is not only a game changer, let's say, but also a change identifier for our profession and for our planet.

Sertaç (right seated) during the Çankaya Healthy Streets project consultation workshop

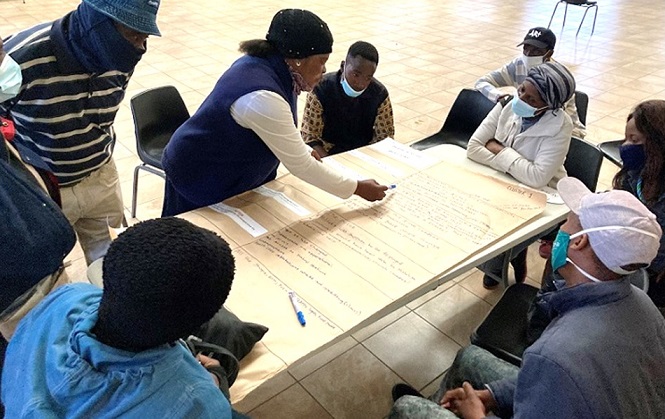

Monique: I think it's really similar to what Sertaç has said. From my perspective, we work on a slightly higher level. We do elements of urban design, but we are working on a more strategic level, a little bit larger than a precinct. And we find that there's a bit of a disconnect between, what our municipalities and what our governments are planning versus what the communities sometimes need and want themselves. One of the things that we've tried to do out of the business as usual is we've really focused on social inclusion and the way that we engage the communities. So, if you look at just the way we've legislated our public participation in our process, it wouldn't necessarily engage the public. If you do, it's more in a cursory manner where you will have your documents printed in a library, you may or may not be required to do a couple of workshops. But there's not a true level of engagement that is meaningful. And as a result, you kind of lose the voices of the community and the various stakeholders by not going down to that level. So, it's been really, really informative for us to, firstly, have that level of engagement, but also to be given the scope within this Programme to really delve deeper into what does meaningful engagement look like, how do you do it? Coming from South Africa, where we've had quite a lot of civil unrest recently in some of these vulnerable communities, and Soweto being one of those, we've looked at how do we repair or redraft the social contract between the city and the community to get them to start trusting one another, to get them to start communicating, and building a relationship. So, it's been really, really powerful for us from a business-as-usual perspective on how we would go about our planning projects. And more than that just also disaggregating our data to be more considerate of gender and social inclusion and exploring these issues together with the different stakeholders and what it means for them. It's been really powerful, if I had to sum it up.

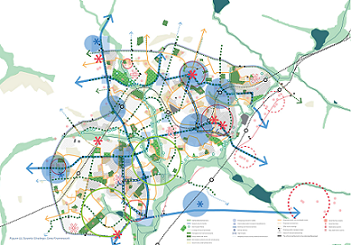

Soweto Strategic Area Framework (SSAF) visualisation

Greg: You're both professionals, providing specific deliverables on these projects and you've seen the execution from the initial scoping to now for the most part of finished product. In what aspects of project planning and execution does taking SDG impacts into account create the most change in your business practices? Is it financial due diligence, cost estimates, procurement, securing project approvals from your client? Where along the way have the fine print, so to speak, of the methodology explored through the Global Future Cities Programme really changed how your companies operate?

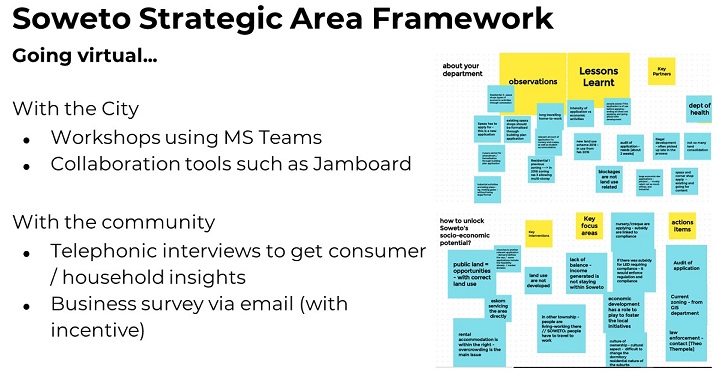

Monique: I think that definitely the project planning and the way in which these projects get costed have been critical, because from the outset, we've specifically gone out and said we want to be highly participatory, we want to achieve these specific objectives. That's what we've done, and we've costed it accordingly. I can tell you now, if this was carried out in a normal way, probably the cost would be considerably less. But we wouldn't have had this amazing output. So, I would say for sure, the project planning plays a huge, huge role in that. And then having very clear outcomes that we want to achieve; our program has really taken advantage of having an agile approach or being adaptive. As situation has unfolded – three months into the project COVID-19 hit, we suddenly couldn't get into the community. We couldn't start with that trust building; we couldn't have these conversations with them face to face. So, we suddenly had to start being innovative and thinking about how we can be doing this. And we kept changing our methodology, we changed our scope a little bit. We thought we would be a lot further down in the process of establishing and kind of formalizing these relationships, which we hadn't been able to do because of COVID, but because of the agile approach that we've adopted, we still made a very meaningful impact, and we still achieved our outcomes. So that has been really great.

SSAF adapting to virtual data collection

Sertaç: Actually, as you say, Greg, there are lots of project stages in urban planning and in urban design. If we take the SDG impacts into account in project planning phases, then we certainly inject sustainability into our project and urban design activities. Of course, I'm speaking again from the lens of urban design, my expertise area, and this refers to localization and landing of high-level SDGs, as effects into local projects. And by this way, sustainable will no longer be like an add-on, but an integrated part of planning activities. To do that, the SDGs should be integrated into the public sector practices very, very early in procurement stages, I think. And if we want to get the most change, sustainable, the principles of each project should be well defined in tender documents and should also be cross-checked in project approvals, which is not a rocket science. And by doing so, design of public spaces, streets, or some neighbourhoods, can be tracked with evidence-based criteria with data, and this will also generate a neutral basis for the evaluation of any urban project, I think.

Greg: Were there any unexpected benefits of incorporating the SDGs into project planning and delivery? You've hinted at some of that already, but are there any specific creative solutions or outcomes from your projects that might not have initially occurred to you were it not for the exercise of going through the SDG Assessment Tool and other components of the Global Future Cities Programme?

Sertaç: My answer is absolutely yes to this question. As you know, the SDG Tool application process to project planning and delivery stages has been conducted with a close coordination and dialogue between key stakeholders. We as ARUP, for instance, as delivery partner, and Çankaya Municipality as a beneficiary partner, came together five times in SDG Tool workshops for healthy streets project, and we assessed the project's activities towards the achievement of the SDG targets in these stages. Following the first stage of tool workshop we, as a team, we got a really deep understanding of this tool and its importance for the city and for us as professionals, let's say, who seek for sustainable design, planning, and engineering solutions at the end of the day. And as the project team, we decided to integrate an approach in designing a new project methodology and that analyses the existing project sites, which is around 10 hectares, to develop some design solutions in that pilot area. This methodology was an attempt to create like an alignment with SDG Tool in the Programme. So, within that, we created eight themes with two subthemes each, and that have been identified to ensure the compliance with the sustainability principles of the tailor-made SDG Tool for the project. And we discussed each theme in detail to provide technical guidance on the different components of streets. And I think, with this new methodology, that we created with a very powerful visual diagram, the municipality had a better understanding of SDGs, their possible reflections, and readings on any urban projects which they will also take care after the Programme ends. And, this is an added value of this Tool to the project, and I'm very happy to experience this.

Visualisation of the selected Çankaya pilot area

Monique: I think that, definitely, the engagement around the Tool led to some really useful discussions and dialogues between us and the city around the various criteria. And I think having the SDG Assessment Tool provides a really good way to look at the theory of change on what are the specific indicators that you need to look at, that feed into the broader principles, that then ultimately feed into the SGD goals. So, that was really, really great to have. And, I think, that in our particular instance and when it came to the social inclusion and the public participation, or stakeholder engagement, it did lead to increased costs. But I don't think it always has to. And I think that one of the ways we could in future, and I'm hypothesizing here, but one of the ways that we could see quite a lot of creativity and innovation in the future is by challenging service providers to be creative within the budgets that we can. Obviously, if it requires significant amount more of your time then you'd need to account for that, but I really think that we could change the way in which we work and we could be more innovative if we just really open ourselves up to it. So, I mean, one of the instances that this new and way of thinking benefited us, and just to give a very specific example: we were engaging the communities on these different topics and having to then delve into the data a lot more and to be inclusive, and to go into GESI (Gender Equality and Social Inclusion), we found out that access to finance was really a major issue. So, taking the guidance from the SGD Tool, we delved into more detail, and we kept seeing, but why? There are already a lot of mechanisms for you to access finance, so, what is the problem? Then we realised, that, actually, it's the issue is the credit ratings and the credit scores, because many people in these communities don't have credit scores. So, they are either unemployed, they've got a criminal record or there are many different instances. And it's those people who are the ones looking for access to finance but can't get it because of the credit rating. So, we need to start looking at non-traditional lenders or how it is that we start rating individuals on their credit, and so led to a completely different type of intervention to what we would have initially had, which would have been a mechanism to access finance. And that's how it's changed through one very specific example in our project.

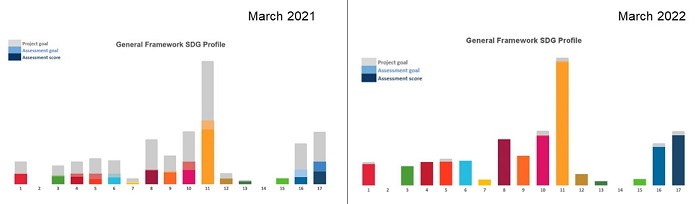

Verification of SSAF progress through SDG Assessment Tool

Greg: When you say a completely different type of mechanism, you had not initially contemplated creating an access to finance product as an initial outcome of the project?

Monique: So, we knew access to finance was an issue. We figured we would just help community members to access the existing finance mechanisms. And then we realised that there was a completely new type of financing mechanism that was required, that would have a completely differentiated credit rating.

Greg: Now what barriers remain in place that prevent urban planning and design firms from factoring SDG impacts into their consulting and advisory services for governments?

Monique: I think, Sertaç actually spoke about it a little earlier. The cities really need to have a good understanding about what they want to achieve. Understanding the SDGs, having it entrenched within their own organizations, and then being able to articulate that in a request for proposals, that they can then put out to service providers to then answer. I they have a very clear understanding, and I mean, everything from what do you actually want to achieve, (and I am taking from our specific example) do you want to engage the community, how many times do you want to see them, what kind of relationship do you want to create with them? And then even the data, we want to have disaggregated data, but is that data actually there, do we have historical data that we can use to compare it against – those all the types of questions that we need to start asking and slowly start entrenching in our organisations. So, from a city side or from a government side, definitely, there would need to be quite a lot of education around and upliftment in what the SDGs are, what kind of indicators, how to use the tools, and how to incorporate principles into planning. And I think from the service provider side, being able to respond to that, also understanding how to incorporate SDGs into your tools, and then just doing it daily, lifting our own standards on how we deliver our work.

SSAF community focus groups workshop

Sertaç: I feel, for me, there is no specific barrier to factoring SDG impacts to specific contexts of different clients. But of course, as you say, Greg, for public sector consultancy, like municipalities or ministries, there's still a reflex of business as usual, like considering first operating expenditures, for instance. So as an example, if a pavement material, standard asphalt is budgetary at that moment for the municipality under some problematic economic conditions, they prefer using this material, though it is a problematic material with its permeability, with its contribution to heat island effect, just as a small example. So, what to do is to figure out a non-capitalizing costs, like social impacts for the municipalities to tackle with these challenges. We, as consultants, should underline social impacts and value for money sides of all decisions to the municipalities.

Greg: Are there elements of how public sector clients can structure their tenders or request for proposals (RFPs), terms of reference, et cetera, that will require adjustments to make SDG delivery an integral component of urban projects going forward? And if you were in the city hall and you were able to write the tender for a company such as yours to respond to, how would you do it differently?

Sertaç: Well, actually, public procurement is, as we know, a powerful tool for sustainable development. Maybe the most powerful tool of local governments, I think. But now in Turkey, for instance, we do not have any tangible practice towards making SDG delivery an integral component of urban projects. But what I would do, let’s say, public procurement and their alignment with the SDGs, I could track them by strategic plans of my sector: if I am a City Hall member, the strategic plans can track the SDGs and how many projects or how many implementations are aligned with which specifications, it can easily attract in local governments. I think, it can be done without waiting for any national, governmental level regulations. I think, this is the power of bottom-up approach for me.

Monique: I must say I fully agree with that, and definitely, the public procurement is a powerful tool for sustainable development, and I don't think that there are any changes necessarily that are required at this stage. But certainly, and I think I spoke about it earlier, if maybe the way in which tenders are written to incorporate the different indicators, that would certainly be helpful.

Greg: Monique, can you tell me about the Soweto project, how did the STG Tool lead your team to disaggregate data and what did you uncover as a result?

|

|

|

Monique: In terms of the disaggregated data, it certainly was insightful to hear or to see what the outcomes were. So, we had a gender and social inclusion specialists on our program who really pushed us to go further and further and disaggregate and to look at our data differently. So, one of the things that we found is that in the study area that we were looking 88 per cent of the residents there who owned land, the residential land, were older than 50 years old. Many of them had received the land from the government, and they weren't using it for annuity income. And so, this presented a huge opportunity for us to really help these community members to secure some form of annuity income through backyard rentals, which they had informally. Through our interventions we could help them to formalize it, get their back-yarding dwellings approved by council, which would offer them security. So, the disaggregation of the data played quite a significant role for our team. And I think in some instances, and I alluded to it earlier, we didn't always have a lot of the data that we were looking for, so we were constantly trying to go out and to source various points of data. Another area of interest for us was really pivotal – informal traders. And there's just no data for informal traders. So, we had focus groups with them to try and better understand what the issues are that they're grappling with, how we can help them, what kind of interventions would be meaningful to make changes. And that was really, really insightful for the team to engage with members of the public to try and understand and get this aggregated data.

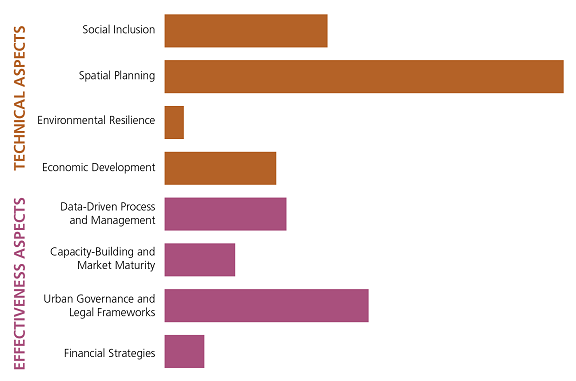

The summary of the SSAF assessment in relation to 8 key drivers, split into Technical & Effectiveness aspects of the project. While the technical aspects show the technical design of the projects, effectiveness aspects focus on the long-term sustainability and impact

Greg: Sertaç, I wanted to focus a little more specifically on Ankara, the Çankaya Healthy Streets project. How did the STG Tool push your team to conduct innovative community engagement?

Çankaya Healthy Streets project: data collection

Sertaç: Well throughout this project, which took two years, as you know, we conducted many participatory methods: design workshops, validation workshops, focus group meetings or consultation meetings, and we applied them to engage various stakeholders to identify not only the existing needs, its neighbourhood and street scale, but also the opportunities and limitations of the city. We tried to make some innovative way to touch them. For instance, we created the decision-making cube game, in which participants analysed different GIS maps of Çankaya, and created their own map on their individual map cards and stick it on one phase of the cube to show which areas should be prioritized for pilot implementation. And of course, the GIS maps were configured in line with SDGs on one hand, and Gender Equality and Social Inclusion on the other hand. All the data was disaggregated with these two umbrella principles, let's say. In our project, we have deliverables under three components. The first one is the urban design services. Here we developed a methodology for measuring the quality of public space, which actually is difficult to qualify. And we developed a healthy streets strategic plan, which covers 36 sub-sections for the municipality. We also designed an urban design pilot project for 10-hectare pilot area. We also produced a manual for pilot project implementation that has a specific section called Sustainability Checklist, and we try to give different ways to the municipality to track sustainability in projects scale, which is something new for the municipality. And the second pillar of this project is the capacity building, as all projects somehow have, and we had training program, municipal networking activity and adaptation of municipal regulatory framework. And again, within that we had special training sessions about different sections of the SDGs. So, we tried to put one more brick on this information. And third one is the dissemination component in this project, and within that, we developed the design manual handbook for healthy streets, which is like the typology for solutions, design solutions. And we did lots of dissemination activities within that, shared these experiences with special relation to the context-based SDG framework. And to sum up, in this dissemination activities, for instance, like seminars, webinars, conferences, academic papers, journals, etc. we always emphasized our two-umbrella principle: one is the Gender Equality and Social Inclusion, and the other is the Sustainable Development Goals and their localization.

Çankaya Healthy Streets project: cosultation with community

Greg: What guardrails such as stronger national enabling legislation or rulemaking in procurement are required to ensure that SDG delivery remains baked into future urban projects at the local level? I mean, if you could design a regulatory framework, what would it look like?

Sertaç: Speaking from my geography, Turkey, there high-level strategic plans of the government, like five-year development co-plans or ministries’ as National Climate Change Strategy, these kinds of documents we have, but there is no landing of these document to the local context, local realities. This is the fact. And so local governments should behave proactively, I think, and should act against climate change with revising their local procurement documents, as I said before, with injecting SDGs and their reflections on local conditions, because they know better these local conditions. And we don't want to hear about, that the SDG, for instance, SDG 11, is sustainable cities and communities, which is everything, and then for me – nothing at the end of the day. But we want to hear about the way to reach SDGs by tracking sustainable principles and key indicators, as we did in SDG Tool experience. I can give an example to concretise this: a procurement document for an open public square, or a waterfront design, can easily include this note for project firms. For instance, we are a private project firm and the municipality can add this note to the tender documents, e.g., “we are seeking for urban design solutions that are climate responsive, ensure comfort and enhance urban resilience”. And not stopping here, this principle can be tracked by the municipality, by the local governments with an indicator that this xxx project utilises urban design solutions to enhance urban resilience through increased soil permeability, drainage, or increasing permeable surfaces, water retention areas, green areas, etc. And the designer or engineering firm can be asked to make its baseline for the existing situation and to show the design solutions in relation to urban resilience, which is missing right now in my geography. How much, for instance, permeable surfaces will be increased, how many new sitting elements will be added to this new design or new engineering solution, how many car parks will turn into besides walk area to have more accessibility for people, for more human centric design solution? These are some examples, and this makes an evidence-based background for climate responsive urban planning and urban design, from a perspective of us, as professionals.

Result of online workshop with children for the Çankaya Healthy Streets Project intervention

Monique: Yes, Sertaç, I do agree with you, and I think that definitely there are high level national strategies and there is definitely advocacy to align with the SDGs, but it's not always in the local context. And again, getting local municipalities more familiar with the Sustainable Development Goals and exactly what it means to align with them, I think, that would be really, really helpful. And then ultimately, for that buy-in to be meaningful, to not just have it as a tick box exercise, but to really get them to engage and understand what it means. Sertaç has given a fantastic example about what it would mean to bring those types of solutions into any kind of project, or into this principle. So I do agree with what she said as well.

Visions of Soweto Strategic Area Framework and Çankaya Healthy Streets project

Greg: Any additional concluding thoughts either of you would like to share?

Monique: So, I think that, from a personal perspective, it's been immensely insightful and such a rich learning experience for me as a person, for my entire team. And I think for the city that we've been working with, who's the beneficiary, at the end of the day, we've all really grown in our own professional capacities having gone through this exercise of engaging the cities and the communities, and stakeholders more meaningfully looking at disaggregated data. If I just look at our end product, it is so vastly different to anything we've ever seen in planning in South Africa ever before. We have got chapters solely dedicated to gender and social inclusion, how we've addressed it, what the limitations have been, and the city asked us, please, include this typical aspect, because we want to know where we've gone wrong so that we can use this as a learning tool for the next project. We've also included a chapter specifically for co-creation and engaging the community, which is something that we've never seen before in our documents. And ultimately, what we really want to see at the end of the day is that we improve our planning so that we can improve our implementation and actually get to implementation. And I think that our entire team and the Programme as a whole has got really high hopes for the product that we've delivered in Soweto, that we are going to see implementation at the end of the day and see a difference.

Sertaç: Yes, I totally agree with Monique. We grew up together with our beneficiary partner, with our team, with ourselves. It's like a maturity process for all of us as professionals, and we learned a lot really in this process and with self-assessing what we are producing or developing for the city and assessed or tracked by the clients – the municipality and also UK FCDO, and of course, with UN-Habitat, it was really great experience, which I have never got before. So, this Programme is like proactive shift, as putting a newly developed perspective and framework for sustainable urban development, let's say.

Greg: That concludes this episode of the Global Future Cities podcast. I would like to thank both of our guests today: Monique Cranna is the Technical Director for Urban Planning at Zutari and is based in Johannesburg, South Africa. Sertaç Erten is the Planning Services Lead at ARUP Turkey and is based in Istanbul. The Global Future Cities Programme is a project of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) working for a better urban future, conducted in partnership with United Kingdom's Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (UK FCDO). This multi-year collaboration seeks to better align the delivery of urban infrastructure projects in middle-income countries with the Sustainable Development Goals.

The three-part Global Future Cities podcast provides listeners with an inside look at how the Global Future Cities Programme (GFCP) has facilitated the design and implementation of sustainable, multi-stakeholder urban projects across the world. Please listen and read the Episode 1 and Episode 3.

Partner

Arup

The Future Cities South Africa programme (FCSA)

Country

Republic of Turkey

Republic of South Africa

City

Ankara

Johannesburg

Themes

Economic Development

Social Inclusion

Strategy & Planning

Data Systems

Author(s)

Gregory Scruggs

Urban Journalist, Communications Professional

Soweto SAF Framework

Soweto SAF Framework  Soweto

Soweto