Global Future Cities podcast, Episode 1: Building an SDG-oriented Global Future Cities Programme

The three-part Global Future Cities podcast provides listeners with an inside look at how the Global Future Cities Programme (GFCP) has facilitated the design and implementation of sustainable, multi-stakeholder urban projects across the world. In the first episode, representatives from the programme’s strategic partners – UN-Habitat and the UK's Built Environment Advisory Group (UKBEAG) – reflect on the approach, challenges, and learnings they observed and experienced while implementing the GFCP. Two senior managers from UN-Habitat, Shipra Narang Suri and Naomi Hoogervorst, are joined by Peter Oborn, a Chartered Architect and UKBEAG co-founder, for an in-depth conversation on successful strategies for capacity building, project financing, and localisation of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Further information and in-depth learnings from the Global Future Cities Programme’s experience are available in the two Programme's Narrative Reports “Partnering for Transformative SDG-Oriented Urban Development: Guidance for Multi-Partner Initiatives from the Global Future Cities Programme” and “Integrating the SDGs in Urban Project Design: Recommendations from the Global Future Cities Programme”.

Below is the transcript of the podcast. Please listen to the podcast here.

Hello and welcome to the Global Future Cities podcast brought to you by UN-Habitat for a better urban future. My name is Gregory Scruggs, and I will be your host for this three-part podcast that will take you inside the Global Future Cities Programme, a project of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme or UN-Habitat, and the United Kingdom's Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office or UK FCDO. This multi-year collaboration seeks to better align the delivery of urban infrastructure projects in middle-income countries with the Sustainable Development Goals. For the unfamiliar, the Sustainable Development Goals, also known as the SDGs or the Global Goals, are a set of 17 aspirations agreed upon by all 193 member states of the United Nations back in 2015. These ambitious goals call for countries to work toward ending poverty and hunger, providing universal health care and education, slowing climate change, and ensuring gender equality, among other important objectives for a sustainable planet, all by 2030. Six years into this agenda, the clock is ticking. And here at UN-Habitat, we believe that cities, home to a majority of the world's population, are essential to delivering on the promise of the global goals.

In the Global Future Cities Programme, private sector companies from some of the world's top urban planning and design firms have been working hard to deliver 31 projects across 10 countries. Their clients, in turn, are local governments who are on the front lines of delivering sustainable development in their communities. Such public private partnership is nothing new in the world of urban development, but the Global Future Cities Programme aims to interrupt business as usual by bringing the 17 Sustainable Development Goals into the conversation. How can the SDGs change urban projects for the better? That's the subject of our conversations here on the Global Future Cities podcast.

Today, we are joined by three guests. Shipra Narang Suri is the Chief of the Urban Practices Branch at UN-Habitat, and Naomi Hoogervorst is a Senior Urban Planner at UN-Habitat; they are both based in Nairobi. Also joining us is Peter Oborn, a Chartered Architect representing the UK Built Environment Advisory Group, based in London. Shipra, Naomi, Peter, welcome to the Global Future Cities podcast.

Greg: Could you please introduce yourselves briefly and explain your relationship to the Global Future Cities Programme?

|

Shipra: Thanks, Greg, great to be a part of this program. I'm a planner by training, I'm the Chief of the Urban Practices Branch at UN-Habitat, which is the home of UN-Habitat’s normative work and global programming. The branch itself has five sections, one of which focuses on planning, finance, and economy, and also hosts our Urban Lab. The Global Future Cities Programme rests within that section, the Planning, Finance, and Economy Section and works within the Urban Lab. And I'm the overall manager for this portfolio in UN-Habitat. |

|

Naomi: Thank you, Gregory. My role is since the beginning of the program in 2018, when UN-Habitat was involved to co-manage this Programme. I'm a trained architect, working a lot on participatory planning, first, in more European context and then later in Kenya, Palestine, Afghanistan, ending up in this Global Future Cities Programme. |

|

Peter: Hi, thanks, Greg. I was the inaugural chair of the UK Built Environment Advisory Group (UKBEAG), which is a collaboration between the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI), the Institution of Structural Engineers (IStructE) and the Landscape Institute (LI) here in the UK. And really recognizing the nature and scale of the challenge posed by rapid urbanization and climate change, our aim is to make built environment expertise much more readily available to national governments together with development partners. |

And we've been involved with the Global Future Cities Programme from the outset, working in partnership with the UN-Habitat to provide strategic capacity development, the aim of which is to use the projects as an entry point to try and engage with some of the other challenges being faced in the cities.

Greg: Wonderful. Stepping back, a big picture question: why focus on cities in emerging economies in the first place?

Shipra: Well, maybe I can dive in here. Greg, you’ve just said the world is more than 50 per cent urban and it's going very, very fast on the path to urbanization. Emerging economies is where managing urbanization, planning, and managing urbanization well, or not, will make all the difference. It will make all the difference in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, and it will make all the difference in achieving both climate mitigation as well as adaptation. The cities, that are included in the Future Cities Programme, offer a real, diverse range of contexts. They are from Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, Western Asia, South-East Asia. They vary in size, in age, in economic phases. So, they offer a real spectrum of urbanisation patterns in emerging economies. And that's where the difference will be made, whether it's in, any continent around the world.

Greg: Why, to your knowledge, did the UK FCDO choose to pursue an investment programme in cities in emerging economies?

Peter: It's an interesting question, Greg, and it's got an interesting answer, I think, because certainly speaking myself as an architect. Because the origins of the Global Future Cities Programme from the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office's perspective, as it was then, was that it was actually a product of the UK's 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Review. Not somewhere you would expect to see cities mentioned, but in that Defence and Security Review, it was recognised that rapid and unplanned urbanization, is among the drivers of instability. And of course, instability creates migration and migration creates challenges. So, but on the other hand, well-planned cities can be a source of social, economic, and environmental wellbeing. So, the Global Future Cities Programme formed part of a basket of programmes referred to as the Prosperity Fund, to which the UK Government allocated 1.3 billion pounds. So, it's a significant programme and the whole purpose of which was to promote economic development as a driver of development in partner countries. So, it was very surprising to me as an architect to discover that that's where it came from. But I think it signals, the importance of this issue in the global context.

Naomi: What's important is that the Foreign and Commonwealth Office at that time, now it's included with development. So, the Foreign Office joined with development arm of the UK. So, we work together with the focal points programme managers from the UK on the ground in their embassies and high commissions. So, there's that sort of additional collaboration, we have on the ground the cities, the UK representatives, the delivery partner, and UN-Habitat – all working together to strengthen relations and build towards sustainability. And I think that was really helpful.

Greg: Heading into the Global Future Cities Program, what was your expectation of the level of engagement with the Sustainable Development Goals, both among these private sector delivery partners and the public sector, the local authorities who were contracting the work?

Naomi: When we were developing the Programme, we saw the trends happening in cities, global challenges occurring, and how can cities improve their planning and management systems to tackle these issues, like inequality, poverty, climate change, health issues. So that's something that we considered, how can we actually make use of this SDG framework to tackle those challenges in a holistic matter. But we also expected that on the local level, the awareness on the SDGs was not that high. And I think that was also what we saw when entering, when starting the discussions with the local authorities, that often there was a lack of knowledge on the SDGs, but especially, on how to implement them on local level. They heard about the goals, but they thought maybe it's more on something abstract on a national level. It was really interesting actually to discuss their goals and actually identifying that in some cases were already working on the SDGs. But now together we started to work with them, leveraging the goals to push forward their ambitions in the cities on sustainability.

SDG alignment of the Global Future Cities Programme

Peter: Speaking on behalf of my own constituency, I think we need to acknowledge that we weren't very up to speed with the SDGs in terms of really understanding that they had practical application. They are international policy, but what do they actually mean to people on the ground? And I think, we've also learned through this process that they do have real leverage, sustainable projects are bankable projects, so they have huge importance. And I think that is one really prominent aspect of the program in terms of grounding in the SDGs in practice.

Shipra: I think a contrast: those views with the growing universal, near universal recognition that the SDGs will not be achieved unless they are achieved in cities. And how do you make sure they are achieved in cities? You make sure by advancing a concept what we call SDG localization, which is really the embrace of the SDGs at the local level by all local actors, not just local governments, but as Peter just said, planners, architects, engineers, built environment professionals, but also communities, civil society, academia, building up an understanding of the SDGs, building up an understanding of what they mean for the local context and also building up an ownership of the SDGs, that what I do makes a difference at the global level. That was very much, I think, a part of this Program and has now been scaled up through several our other programs.

Greg: You expected fairly low levels of engagement with the SDGs. How did the urban project delivery rolled out through the Global Future Cities Programme ultimately compare with those expectations?

Naomi: I think we all have a sort of learning process together. I must say developing this SDG Tool, based on policy guidance, standards that were already there, bring them to the local context and linking them to the SDGs on target level - so that's really on the level of understanding how, for example, sustainable transport can help more people to access transport in their own neighbourhoods. And I think when learning together, we changed our mindsets, all of us.

Greg: Can you describe this mindset shift and how it was perhaps different for different actors in the Programme?

Naomi: Yeah, I think that's quite something to say, actually, about this, because for some cities, it's still a challenge actually to understand this, this bigger picture, this bigger framework. So, we try to simplify it based on the context and the capacity of the city authorities and in some cities, for example, in the context of Turkey where we work, there's a real appetite to learn to make use of that, and there we are in a sort of equal process of working more and more with the SDGs. I think for the delivery partners also saw a difference in working with the SDGs, because what we heard more and more financial institutions need bankable projects, need sustainable projects and some of the private sector partners, they really see that opportunity to they need to change their project designs to make them really sustainable in terms of governance, environment, and social inclusion. So, in some cases it is really working well. I also must say, in some cases, there's also some hesitance from the delivery partners to add something to their outputs. This is really an impact-oriented approach thinking about the long term. And of course, it's not always easy to sort of commit to long term goals, but I think that's where we have to work together with the cities that will take those projects forward in the future.

SDG Tool workshop in Bangkok, Thailand

SDG Tool workshop in Bangkok, Thailand

Peter: Can I just pick up on that because I think you're absolutely right, Naomi. For me, one of the fundamental shifts is that from thinking about deliverables to thinking about outcomes and impacts, and that simple statement brings about all sorts of challenges in terms of encouraging people to work, or requiring people to work, much more collaboratively, as you've said, to break out of their silos, to think more holistically in terms of both policy making on the one hand and delivery on the other. And so, I think as you start to become drawn into this issue of engaging with the SDGs, it inevitably engages you with some of those challenges, which, as you've said, in some of the cities, it's been easier to address then in others.

Greg: I'd be curious to hear a brief reflection on the private sector, these delivery partners. To what extent were the SDGs part of their business practice? How did they adjust to incorporate the SDGs into their line of work?

Naomi: There's a need for the private sector to have those SDGs and also the sort of collaborative process from the onset in their terms of reference, in their project descriptions, because otherwise it will add to the costs, and they have to deliver. And that's also from their side, it's understandable. So, that's something that we got as feedback for from the private sector partners. But I think still there is room to integrate, it doesn't have to cost more. It's sometimes looking at synergies or sustainability should be there often, if we have the objectives of the program, that's around a sustainable urban development and inclusive prosperity.

Peter: I think it's probably fair to say, and I don't know if Naomi would agree with me, but we've all been on a bit of a learning journey throughout the life of this project. UN-Habitat, ourselves, and the cities - we've been on this journey together, and I'm just reflecting on the timing of this conversation and the fact that it's not long after COP26 has finished. I was really interested to read in the news that business was complaining that governments weren't going far enough, fast enough. And I think that's a kind of measure of the way in which business and the private sector is responding to the goals, because they're recognizing now that the targets which we're all seeking to achieve have a value beyond the financial, but they also have a financial value. And in terms of work winning, in terms of work delivery, there's no doubt that the global goals are gaining increasing traction in business and beginning to change the way in which business is done.

Naomi: To add also in the benefit of the delivery partners in our collaboration, which is key to scale up our work to have more of these sort of multi-stakeholder programs, is that they also saw a lot of opportunities to make sure that the cities are also collaborating with their national governments. If there is a sort of a push from the national governments to work with their cities on localizing SDGs, that will really help us to replicate this work, scale up, and make sure it's done throughout their countries.

Greg: I want to ask Peter about Bristol in the UK and what lessons, which they have experienced with the SDGs, while integrating into city governance, offers for the kind of cities, that are featured in the Global Future Cities Programme?

Peter: Sure. And just to maybe explain that Bristol has featured as part of our capacity development activity, and Mayor Rees has contributed to a number of the sessions and has proved to be a very popular contributor, because of the way in which their plan has been developed, which is very accessible. And maybe just to say something quickly about Bristol in terms of its size and its scale. It's the 10th largest city in the UK. It's one of the 11 core cities in the UK, with a population of about half a million. It has its own challenges. It has 17 per cent of its children under 16 live in low-income families. It has a flood vulnerability, so it has several the characteristics, which some of the cities that we're talking about. A current Mayor, elected in 2016, Mayor Marvin Rees, inherited a legacy of hundreds of unaligned city strategies, many of which had a kind of quite a short time frame, and there was no framework for bringing together city partners. So, his response was to develop what they now refer to as the One City vision. And basically, they brought together city partners and created this One City Vision, which kind of sequences activity up to 2050. And to accompany that, they created a City Leadership Framework. They looked at all their existing city strategies, they opened a dialogue with the public, they held discussions with over 100 city stakeholders. And they began to sort of map local challenges against the global context by which I mean the SDGs. So, they used the SDGs as a framework against which to kind of calibrate themselves and their plans going forwards.

Greg: Can you highlight specific projects or cities from the Global Future Cities Programme that offer particularly strong examples of how the public and private sectors can work together going forward to incorporate the SDGs into urban project delivery?

Lagos, Nigeria

Lagos, Nigeria

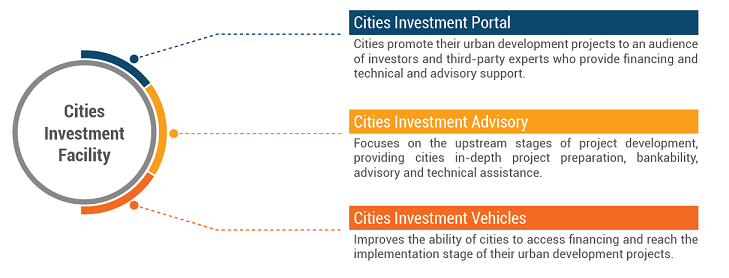

Naomi: I think an inspiring project is taking place in Ankara, in Turkey, where there's an implementation plan of a bicycle network in the municipality, on metropolitan level and we received a lot of feedback that this tool really helped improve the project. They had technical discussions, what does some of these sustainability principles mean, how can they address it. So, I think we learned a lot from the discussions in Turkey, and that's also what they are now trying to use for other projects and with other stakeholders. So, there are discussions in Turkey on how to really replicate this type of work. Another example, that's inspiring, is in Lagos, Nigeria. I think we all know, there are challenges, but one of the objectives is to also increase a more sustainable transport modes, and one of them is through water. So, there's a Lagos water transport feasibility project as part of this Programme. And I think these SDGs really frame the discussion around accessibility to vulnerable groups. So, for example, persons with disabilities are engaged in the process to really ensure that there's a sort of universal design in developing those transport systems over water and that's accessible for themselves as well. And what's also an interesting outcome of this process is the next step to have discussions with the financial institutions. The private sector partners – Future Cities Nigeria, is really keen to help the city through sort of investor summits to make sure that there's a sort of matchmaking being done with financial institutions, making sure that the right documents are in place. And also, this project is part of our Cities Investment Facility (CIF), an initiative from UN-Habitat to also help to create more bankable, viable projects in urban development. And perhaps, Shipra, if you would like to say something about that.

The three instruments of UN-Habitat’s Cities Investment Facility

Shipra: Yes, if I can build on, it's very, very interesting to have this conversation because sometimes you need to dive deep into projects, but you also need to zoom out and see where the big picture is. For me and for us in UN-Habitat, generally, we've seen a lot of innovation from cities. We've seen a lot of interest from private sector partners. I've seen a lot of commitment from local governments, but very often the big gap, the big weakness that happens, is between the local and national policy environments. The enabling environment, we talked about it in the beginning, is often just not there. The policies, the legislation, the financing mechanisms, the resources available to cities, their ability to tap into markets, their ability to get loans, and their ability to work with the private sector independently is often very, very constrained. And I think, what we're trying to do both through the Future Cities Programme, but also through our other programming, and this is where the Cities Investment Facility also comes in, is to invest a lot of time and on one side, helping to create bankable projects, but on the other side, helping to create structures, policy environments, legislative structures and change mindsets at the national level, which allow more and more delegation and empowerment of local governments and local actors. That is really still the missing piece when we talk about localization. Just while I'm at it, the point that Peter was making a little earlier about Bristol and were talking about the Voluntary Local Review that Bristol has done, it's really a leading light in that sense. And we have seen that Voluntary Local Reviews are becoming another instrument for local governments to engage national governments. UN-Habitat is assisting and facilitating that process. Very many times, because national governments have the responsibility to report on SDG achievement through Voluntary National Reviews (VNR) and the early generation of VNRs, as we call them, never really looked at the local context, never really engaged the local actors, never really offered nuance in where the SDGs were being achieved in their country and in which areas were left behind. So, in some ways, data was, as data tends to do, was hiding more than it was revealing. But when local governments started to report on SDGs, then they started adding that value and that nuance, and it became a very important instrument for enhancing this multilevel governance and multilevel cooperation. That, to me, is still the missing piece. You can have great projects, you can have great private sector interest, but if you don't have the environment within which to combine the two, we're not going to see progress.

Greg: Naomi, you've mentioned a few times already the SDG Tool. What is the SDG Tool and why is it such an important innovation in this program?

Naomi: So, the SDG Tool is a framework instrument and together a sort of process to help improve the quality of projects to also create a better enabling environment. That's, I think, what we discussed more on governance and financial strategies. And thirdly, this participatory process, these guidelines on how to collaborate in discussing the SDGs in projects. It has a 54 and sustainability principles, and those sustainability principles are derived from global publications and standards on sustainable urbanisation, and they are linked to the SDG targets. So, that's sort of the framework that we're working with and for each of the projects we can select with the partners, the sustainability principles that we think the project should address. And then after that selection, I think the tool helps to create an SDG project profile so you can actually see to watch as to which as the GS, the two the project is contributing to.

Peter Oborn (center) with capacity building workshop participants at Royal Institute of British Architect (RIBA)

Peter Oborn (center) with capacity building workshop participants at Royal Institute of British Architect (RIBA)

Peter: The capacity building programme, that we've jointly developed, has really identified six key themes which have been found to be common to a greater extent to all the cities. And they are:

(1) integrated and inclusive planning. When we boil this down to practice, we find that, a lot of cities are still working in silos, they're not working effectively across departments. So, that degree of integration is missing. They're not practicing participatory planning, it's not particularly inclusive.

(2) the second is governance and collaboration, which I think we've talked about already in this session. But governance and collaboration not only from the perspective of the local government, but also how that alignment with national government works or doesn't work. And there are far too many examples that we can all name of cases where it doesn't work particularly well.

(3) evidence-based design and the effective use of data. There is an increasing awareness about the importance of data, but not an increasing awareness or corresponding awareness of how to use it effective. So, I think using data effectively is really important, and we've been focusing on that and our programme.

(4) project finance and procurement; where do you get the money from, how do you make the case to your funder, whether it be government or lenders to actually obtain the money. And of course, as Shipra said, you know, long term finance is the Achilles heel of so much of the work that we're doing in terms of its lack of availability, local government procurement. How do you then buy the project on in the way that you can ensure you get what you're expecting?

(5) and then last, but no means least, implementation and enforcement monitoring, and evaluation. How do you actually make sure that people are doing things for impact, not just for compliance? There's a lot of compliance work being done for the sake of achieving some sort of regulatory environment, but not necessarily achieving outcomes and then monitoring and evaluation: how do you actually keep track of things and make sure that you actually deliver what you intended to do?

(6) and then finally, the sixth theme which has emerged through our series, which I guess we should have thought about at the outset, but really has come as a natural consequence of the program. And that's leadership and change management: who is actually going to help make these shifts that we know we all need? And that really has become the dominant theme of our program.

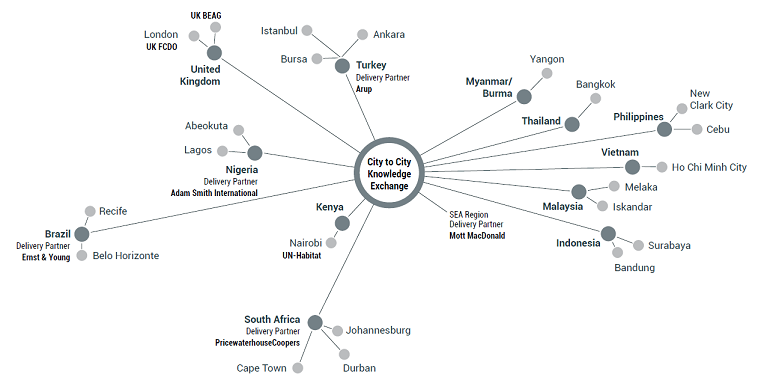

City-to-City Knowledge Exchange capacity building component

City-to-City Knowledge Exchange capacity building component

Shipra: Can I come in on leadership for a second? I think it's very important. Typically, political leadership in any country is, you know, four years, five years in a city. How do you make sure that there is widespread ownership beyond the political tenure of one party, one term, one mayor? How do you do that? And this, in our experience, both in the Global Future Cities Programme as well as others, we do this through building broad based coalitions of stakeholders and developing collective vision. So, a lot of time, a huge amount of time, pre-investment - we call it actually project time – was spent in that initial process: advocacy, visioning, collective visioning, collective prioritization. So, that the projects we are identifying are not just related to the vision of one mayor or one political leader, but they have a long life, they're sustainable beyond these political tenures. And I think that is a very big dimension of sustainability that we've seen in these projects.

Peter: And I just go back to Bristol as an example. This idea of co-creation, I think, is really important. Co-creation, joint ownership and that sense of common purpose and having a horizon, which is sufficiently far ahead. And this again, is where the SDGs create that horizon. 2030 is a great horizon to aim for. So that sense of common purpose is vital. And then the other component I would just add into the mix, is prioritization, because you can't do everything at once. So, what do you do first or what do you do next, I think is also important. One must recognize, you know, we all have limited limitations in terms of our working environment. So, what is the most important thing to do next.

Shipra: Or the most catalytic, because important – yes, and many things will be important. But what is that one thing or what is that one project, or what is that set of interventions that will have multiple impacts on different SDGs? You know, when you talk about a public space intervention, when you talk about the public transport intervention, it has an impact on equity. It has an impact on livelihoods there for poverty reduction. It has an impact on climate, has an impact on all dimensions of SDG 11, but also beyond the goal on cities. So, we have to find those interventions that hit multiple targets and have multiple impacts with just that single investment. And I think that's critical for cities when you talk about prioritization.

Peter: Yes, that's a really good point, Shipra, because I think going back to Naomi's example of the Lagos Waterways project, I think that's a great example of a project which is catalytic in the sense that it serves a direct purpose in terms of reducing congestion, but in turn, that reduces pollution, in turn, that increases economic performance, it opens up the prospect for regeneration, for transport or into development. Just as you say, catalytic projects are key.

Greg: I think I'm going to move to our concluding question. At the end of the day, to what extent did the Global Future Cities Programme succeed in changing the business-as-usual mindset? I would say, both among the private sector players, who are likely to deliver the bulk of the world's future urban infrastructure, and the public sector players and the client, who will be soliciting that infrastructure?

Peter: My answer to that question is very straightforward, and that is, I think what we have achieved through the Programme is demonstrating that sustainable projects, as we've said before, are bankable projects, bankable projects, or fundable projects. Fundable projects are deliverable projects, and you need deliverable projects to achieve impact. And I think through that kind of that chain cities are waking up to the realization that the SDGs are actually really, really important.

Shipra: For me, I think the one thing that the Future Cities Programme has shown that the SDGs can be the guiding framework for everybody. They are not just these lofty goals adopted by the U.N., the SDGs are and continue to be our robust guiding framework at all levels for all stakeholders, for all urban actors and for cities. Because sometimes there's also a question of whether some of these goals relate to all cities and, we know, that 65-70 per cent of the SDG targets are directly related to cities. But a city is an abstract notion. A city is not an actor. A city is not a doer. There are multiple doers in cities, and all those doers have to embrace the Sustainable Development Goals as their guiding framework. What the Future Cities Programme has done is unprecedented, really, it provides that opportunity to stakeholders to understand and embrace the SDGs and take them forward. So, I think that has been, if I were to count one among all the different achievements of the program, I would say that's the most important one.

Naomi: And maybe I can add to this, I think what's also important of this Programme is that we, in the end, brought cities together not only networking, but really on sort of the working level to exchange knowledge. And the SDGs are a good common language to do that.

Shipra: And on that, let me make a plug for UN-Habitat. At this point, we work broadly, we work in 90 odd countries around the world, in many, many, many different cities. And I think, Peter and Naomi, your work, the UK Built Environment Group’s work for the Future Cities Programme, has really offered an opportunity and opened a door for all the hundreds of cities, thousands of cities that we work with and offered a model of the pathway for them to adopt and use, and leverage the SDGs. So, thank you for that.

SDG Tool workshop in Durban, South Africa

Greg: On that note, we will conclude today’s episode of the Global Future Cities podcasts. I would like to thank all three of our guests: Shipra Narang Suri is the Chief of the Urban Practices Branch at UN-Habitat, and Naomi Hoogervorst is a Senior Urban Planner, also at UN-Habitat; they are both based in Nairobi. Also joining us today was Peter Oborn, a London-based Chartered Architect representing the UK Built Environment Advisory Group.

The Global Future Cities Programme is a project of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) working for a better urban future, executed in collaboration with United Kingdom's Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (UK FCDO).

Partner

UK Built Environment Advisory Group

Themes

Spatial Planning

Climate Change

Data-Driven Process and Management

Financial Strategies

Social Inclusion

Strategy & Planning

Author(s)

Gregory Scruggs

Urban Journalist, Communications Professional