Towards socially inclusive urban development: lessons learned from the Global Future Cities Programme

“Each and every person should have access to all the benefits that come out of development with no one person being left behind” – Dr Theresa Devasahayam, a Gender and Social Inclusion (GESI) Specialist from Thailand with 24 years of experience in gender issues.

As part of United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office Global Future Cities Programme (GFCP) has been carrying out technical assistance for a set of targeted urban interventions to encourage sustainable development and increase inclusive prosperity. The programme operates across 19 cities in 10 countries, where various urban projects have been developed, based on three thematic pillars: urban planning, transport, and resilience. The promotion of inclusive urban development and addressing gender equality stands out as a key premise of the programme. In that sense, substantial efforts have been made to mainstream gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) across all interventions and throughout multiple project phases.

As a key strategic and capacity building partner of the GFCP, UN-Habitat's Urban Lab has been providing strategic advice and technical recommendations to ensure interventions are inclusive leaving no one behind, in line with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the New Urban Agenda. Such an approach resonates with UN-Habitat’s commitment towards social inclusion, which is mainly focused on human rights, gender, children, youth and elderly, also persons with disabilities.

The Urban Lab’s integrated and impact-oriented planning approach ensured mainstreaming social inclusion in the different urban interventions. As such, social inclusion is understood as both an outcome and a process that entails removing barriers and preventing the construction of barriers, so that everyone has equal access to the goods, services and opportunities cities have to offer. Additionally, social inclusion is about enabling multiple voices to be heard, especially from people in disadvantaged situations and those directly impacted by urban projects, towards fostering democratic and participatory decision-making in cities.

Throughout the GFCP, UN-Habitat has been promoting the localization of social inclusion objectives by applying the SDG Project Assessment Tool (SDG Tool), which is an offline, digital and user-friendly instrument that guides City Authorities (CAs) and Delivery Partners (DPs) in the development of more inclusive, sustainable and effective urban projects. The tool is applied through a collaborative methodology, in which individual assessments are discussed in interactive sessions, towards achieving recommendations for project improvement. Besides social inclusion, the tool also addresses other issues, such as environmental resilience, governance, legislation, and finance, linking inclusivity with other key drivers of sustainable development.

The SDG Tool has contributed to the social inclusion dimension of projects over time, by providing guidance from the beginning and across various project design stages. On one hand, the tool presents concrete ideas and clear targets around social inclusion, which has influenced substantially the pathway followed the interventions. On the other hand, the tool allows stakeholders to understand the bigger picture and think of overall strategies that make cities more inclusive.

Why social inclusion?

The GFCP projects take place within a heterogeneity of territorial, cultural, and political contexts, as well as multiple thematic scopes. Some municipalities had inclusive urban planning in their agenda prior to the GFCP. For instance, Belo Horizonte (Brazil) has been promoting gender equality in public transport, and such political intention has unfolded through the Intelligent Mobility in Expresso Amazonas project. Inclusive urban development has also been on political agendas at a national level, like in the case of Turkey, where over the last decade there has been an increased focus on participatory urban planning. Such an national ambition has been catalysed by Istanbul’s Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (SUMP), which has a highly participatory character.

Notwithstanding, in some contexts, social inclusion has not been given substantial emphasis and considered less urgent when compared with other critical issues. For example, in Lagos (Nigeria) it has not been common to directly involve low-income groups in urban planning processes. Thus the Guidelines for Urban Renewal in Lagos have been encouraging more engagement with such groups, especially residents of informal settlements. Similar experience is encouraged in South Africa under GFCP partner’s Future Cities South Africa programme (FCSA) intervention.

At the level of the projects themselves and their thematic scope, some interventions have social inclusion as a core objective. Such a focus becomes more evident in urban planning and design interventions, where community participation can directly influence spatial design solutions. For example, the Urban Transformation Plan for Putat Jaya in Surabaya (Indonesia) clearly applies a people-centred approach aiming at social transformations through urban design. Other projects have a more technical character, and the relevance of social inclusion is not so evident, such as the Development of a Geographical Information System for the Drainage System in Ho Chi Min City (Vietnam). The GFCP has been mainstreaming social inclusion even in such technically driven interventions, for example by incorporating vulnerability criteria when mapping flood-prone areas.

Therefore, when it comes to inclusive approaches, all projects benefit from being under the umbrella of a programme such as the GFCP. Social inclusion has been clearly emphasized as a key driver of sustainable development at programme level, projects have been constantly assessed as they evolved through the SDG Tool, which has a strong focus on social inclusion and points to specific directions to be taken towards making interventions more inclusive. Collecting data for socially inclusive urban development

Collecting data for socially inclusive urban development

Projects have been applying multiple strategies to ensure that voices of disadvantaged groups are heard, to guarantee meaningful participation and to work towards the removal of barriers. For example, in Iskandar (Malaysia), a Citizen Feedback Portal is being piloted, allowing citizens to submit geo-referenced complains and make comments about various urban issues. In the Development of a Smart Ticketing System in Ho Chi Mihn City (Vietnam) the results of a survey with users have substantially informed recommendations for more inclusive solutions.

The GFCP through the SDG Tool has also been putting a strong emphasis on data disaggregation, which helps accurately understanding the demands and needs from specific groups, according to gender, age, disability, income, and social status. In Iskandar (Malaysia) DPs have developed an application, which supports the collection of disaggregated data through surveys with a wide range of residents.

Involving affected communities throughout project phases

Apart from a comprehensive understanding of the existing situation, involving affected communities throughout different project design phases stand out as a fundamental driver of social inclusion. The organization and maintenance of focus groups discussions with specific target groups, such as women, youth, or elder persons, has been an essential strategy in different projects of the GFCP to increase the ownership by project beneficiaries. Focus group discussions have been used as an effective mechanism for a more collaborative achievement of solutions.

Focus Group Discussion with the local vulnerable group in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Also, a series of participatory charrettes and workshops have been hosted with the stakeholders involved. Such a strategy encourages the identification of specific issues faced by local communities, that would otherwise be neglected by urban professionals. Prior to participatory processes, capacity building activities have been usually delivered, so that participants have a good understanding of what will be discussed. Moreover, it has been fundamental to partner with existing community-based organizations and NGOs, which have existing connections and in-depth knowledge of the local context.

Engaging priority groups

Reaching disadvantaged groups and developing specific solutions that attend to their needs is a major challenge in urban planning and development and should be on the agenda of any sustainable urban transformation. In the GFCP, substantial attention has been paid to addressing the needs of target groups, especially women, persons with disabilities, children, youth, elder persons, informal workers, migrants, and low-income communities.

GFCP projects have been addressing specific needs of women as pedestrians when carrying trolleys or the necessity for improved lightning to increase safety. In Ankara’s (Turkey) Increasing Quality and Accessibility of Streets in Çankaya Neighbourhoods women were heard through participatory workshops, leading to specific design solutions near metro stations and schools to increase safety.

Participatory workshop in the Çankaya Healthy Streets Intervention, Ankara (Turkey)

In the Lagos (Nigeria) Water Transport project, persons with disabilities were directly involved in participatory processes and the transport interventions will guarantee their accessibility through universal design. The Earthquake Preparedness Strategy for Surabaya (Indonesia) tailor-trained persons with disabilities as this group was not previously aware of earthquake preparedness. In Ho Chi Mihn City (Vietnam) persons with disabilities were consulted for more inclusive public transport through focus group discussions.

Involving and targeting people from diverse age groups is also crucial for enhancing the social inclusivity of interventions. In Ankara’s (Turkey) Increasing Quality and Accessibility of Streets in Çankaya Neighbourhoods, a series of workshops have been organized with children living in the pilot implementation area. As a result, the intervention will address children's needs by improving street crossings and promoting pedestrianization of streets, so that their journey to school becomes safer. In another example, the Lagos (Nigeria) Water Transport project has been proposing new transport networks that account for the specific routes of youth groups when commuting to school, as well as their capacity to pay for each journey. Focus group meetings under Development of an Integrated Public Transport System in Bandung (Indonesia) were addressing issues of elderly.

Result of Online workshop with children for the Çankaya Healthy Streets Intervention, Ankara (Turkey)

A crucial aspect of socially inclusive urban transformations in developing countries is the understanding and careful incorporation of existing informal practices. In many GFCP’s interventions, informal street vendors are being considered when designing urban regeneration of public space. Informal transport providers have also been understood as key stakeholders. For example, in the Development of an Integrated Public Transport System for Bandung (Indonesia), specific strategies are being developed to incorporate and potentially formalize informal transport providers.

Low-income populations is the focus in many GFCP’s interventions with poverty reduction and increased prosperity as one of its key objectives. For example, the Cebu (Philippines) Housing Strategy has been prioritizing housing provision for populations of lower income, who reside in slums or areas of high environmental risk. Furthermore, the Surabaya (Indonesia) Urban Transformation Plan for Putat Jaya has been providing entrepreneurial guidance to low-income micro, small & medium enterprises, in order to promote economic growth in the area. Similar issues are address in Johannesburg’s Soweto under the Strategic Area Framework and Associated Implementation Tools for Soweto “Triangle” in Johannesburg project.

Focus Group Discussion with multiple stakeholders about housing strategies for Cebu (Philippines)

Challenges and solutions arriving after the Covid-19 outbreak

The Covid-19 pandemic hit the countries where the GFCP operates in multiple ways, levels, and times. Regardless of the dimension and temporality of lockdowns and restrictive measures, all projects faced the common challenge to engage with local communities when physical distancing was needed. Such limited engagement has made socially inclusive strategies more difficult. Nevertheless, the circumstances of Covid-19 also allowed for the emergence of innovative solutions, especially around the use of digital technologies.

The GFCP projects have applied innovative solutions to collect data, foster citizen engagement and enhance participation through digital technologies. Remarkably, Delivery Partners have made use of social media platforms that are already used by affected communities daily. For instance, in Recife’s (Brazil) Data Ecosystem for Urban Governance, the free messenger platform WhatsApp was used to contact key stakeholders. Similarly, in the Lagos (Nigeria) Water Transport project a series of WhatsApp groups were created to host focus group discussions with target groups. Such a strategy allows for the engagement of low-income residents who usually have no access to laptops or a fast and stable internet connection and would not be able to attend video conferences. Additionally, in the Housing Strategy for Cebu (Philippines), face-to-face workshops were shifted to an online format whenever physical meetings were not possible, or combined face-to-face with online tools in a hybrid format.

Hybrid meeting combining online and in-presence participants in Cebu (Philippines)

Despite the great potential arising from the use of digital technologies, the GFCP interventions also reveal some limitations in such strategies. On one hand, it has been easier to reach youth groups, who already use social media on a regular basis. Nevertheless, elderly groups are harder to engage, as they might not be so familiar with using smartphones or computers. Moreover, as some UN-Habitat’s Local Strategic Advisors report, the experiences of face-to-face encounters were usually more productive, allowed for easier communication between stakeholders and fostered greater collaboration, in comparison with online participation strategies during the Covid-19 pandemic. Therefore, one important lesson learned from the GFCP is that online community engagement is more productive when combined with physical meetings.

Building Capacity and Sharing Knowledge around Social Inclusion

Developing and applying social inclusion strategies requires good knowledge of best practices and existing guidelines. In that sense, the GFCP has been successful in promoting spaces for knowledge exchange through which fundamental learnings on Social Inclusion are shared. For instance, in Bangkok (Thailand) a capacity building workshop was conducted with City Authorities to present key ideas on Gender Equality and Social Inclusion through practical examples, case studies, and hands-on activities.

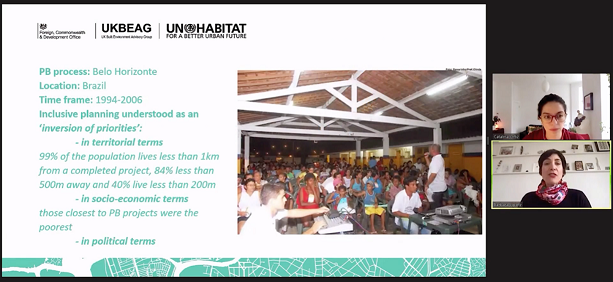

Presentation of inclusive urban planning practices as part of the Thematic Programme of the Capacity Building Component

As a global network of cities, the GFCP has also been providing outstanding opportunities for learning on Social Inclusion, through its capacity building activities. During the Thematic Programme of the Capacity Building Component, delivered by UN-Habitat in partnership with the UK Built Environment Advisory Group (UKBEAG), a session was delivered under the topic “Integrated and Inclusive Urban Planning”. This session addressed integrated and inclusive planning as a crucial mechanism for guiding social, economic, and environmental advancements while accounting for the needs of disadvantaged groups.

Towards long-term social inclusion impacts

GFCP’s focus on social inclusion aims for inclusive cities where specific disadvantaged groups will be empowered and decision-making will become more participatory, benefiting not only directedly affected citizens and communities, but also the urban population as a whole.

Beyond the direct impact of interventions, an important legacy of the GFCP revolves around changing the mindset and building the capacity of City Authorities and Delivery Partners. Through the SDG Tool and the possibility of knowledge exchange with other cities facilitated by the Programme, City Authorities have become more aware of the importance of addressing social inclusion in cities. Moreover, they have been in direct contact with innovative approaches to mainstream social inclusion on the ground. As such, it is expected that this change in mindset and built capacity will be replicated to other urban interventions in the cities and countries of the GFCP, contributing to the achievement of the SDGs and the New Urban Agenda (NUA) in the long run.

This article has been developed from an analysis of semi-structured interviews conducted with Local Strategic Advisors (LSAs) of the Global Future Cities Programme. The interviews gathered perspectives on how social inclusion has been addressed on the ground, as well as challenges and solutions emerging from concrete cases. The interviews were complemented with an analysis of existing documentation of socially inclusive initiatives, such as the stories reported at the GFCP’s knowledge management platform.

Themes

Social Inclusion

Author(s)

Mateus Lira

Social Inclusion and Human Rights Expert, Global Future Cities Programme